By Dan Greene (@Greene_DM)

Last Sunday, I was lucky to be able to convene a panel with my colleagues Laura Portwood-Stacer (NYU), Lisa Nakamura (University of Michigan), Anne Cong-Huyen (UCLA), and Tara McPherson (USC) at the American Studies Association in D.C. that was intended to act as a retrospective on digital cultural studies and a conversation about its future. The plan was to give quick 10 minute talks on current research, and then have Tara respond to them and moderate the discussion. After everything wrapped up—with a packed room on a Sunday, thanks all!—I confessed to the panel that my thinking in bringing everyone together was basically “These are good, critical people who both stand out in the field and know how it works, they’ll have keen observations on the politics of digital communications and and the politics of studying them—we all get along and something good will come out of that.” But I was delighted to see a more focused debate emerge, alongside a series of questions we felt we needed to keep asking: What counts as work and how far can you get by telling someone that their play is work? What gets described as a feature of the social Web and what gets described as a bug? Why are pervasive atmospheres of racism or sexism written off as ‘trolling’? How do we move beyond tired debates of exploitation versus empowerment? Is it ever worth talking about one ‘internet’?

Karen Gregory was kind enough to offer me (@greene_dm) this platform to share our conversation with a broader audience. Below I’m going to quickly summarize each of our talks and some of McPherson’s responses to them before commenting on some of the themes that emerged from our roundtable discussion. The latter includes both the questions above and interventions specific to the field such as a return to Marxist feminists such as Selma James and Silvia Federici, and a turn, prompted by Nakamura’s talk on race and virality and McPherson’s coinage of the phrase, to a ‘critical platform studies’ that moves us from media archeology’s focus on the thing itself to the social infrastructure that makes the thing work or not work in different political and cultural contexts. Please also take a look at the original abstracts for the panel and our talks, as well as Jack Gieseking’s Storify of the Twitter backchannel. Let’s keep talking.

Access to Self and City:

Internet Entrepreneurs and the Politics of Presentation and Space

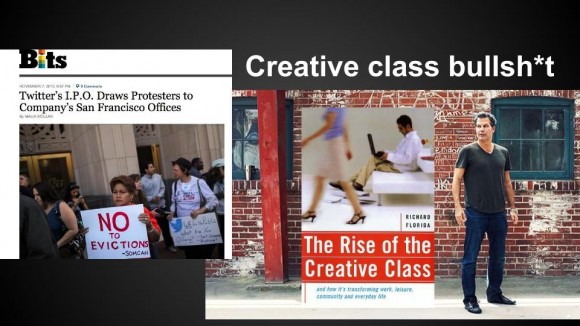

I’m involved in long-term fieldwork with different communities in different positions in Washington, D.C.’s booming information economy. D.C.’s municipal government, like so many other cash-strapped cities, has embraced a version of Richard Florida’s ‘creative class’ policy which pins our economic future on recruiting and maintaining creative class workers—especially the tech entrepreneurs that are the favored sons and daughter of the present moment—through place-making projects that focus on friendly forms of diversity and lifestyle amenities. Working with tech entrepreneurs who design and produce, but also work on and through, various social media platforms, I have been struck by how the production of social media spaces neatly parallels the production of gentrified city spaces through creative class policy. Twitter, Facebook and FourSquare may gentrify our self-presentation in a manner similar to how cities are gentrified by creative class policies, creative workers, and real estate investment designed to capitalize on them.

Tech entrepreneurs often use social media to erase the line between work and play so that every interaction is a potential networking opportunity. Formerly private information is made public in the name of authenticity; though some information, such as political or religious beliefs, is scrubbed in the name of more seamless sharing. This information—where you are, when, with whom—is both a useful interpersonal wedge in business negotiations and the raw material of the data economy. But these social norms end up alienating those who cannot or will not lifestream—including one of my participants who is a new mother. Gentrification of city spaces does not only replace housing stock and push low-income residents out, it is also an uneven process that filters attention to specific high-status areas (i.e., D.C.’s venture capital, condo-building, and restaurant opening booms all overlap in the same 20005 zip code) just as social media creates ‘filter bubbles.’ And just as lifestyle amenities (parks, restaurants, clubs) are the chief place-making recruitment tools of creative class policy, so too are they the chief check-in points for location based social media, and the backgrounds for the most shareable group photos. Why do these overlaps exist? At this early stage, I hazard a guess that both social media and gentrification act as ‘spatial fixes’ for desperate capital: social media outsources value production to previously uncapitalized areas of everyday life and provides a profit-making opportunity via speculation in unprofitable companies; while gentrification of downtown D.C. kicked off during the recession, when other real estate markets were tanking, and already shows signs of a potential speculative bubble not unlike that in social media companies. So it looks like creative class policy, and the cultural and financial hype over creative workers, may actually be a symptom of capitalist crisis (the addict’s search for a ‘fix’) rather than a bulwark against it.

The Work of Social Media Refusal:

Thoughts on Labor, Productivity, and Identity among Facebook Resisters

Laura Portwood-Stacer (@lportwoodstacer) just published a book on lifestyle activism in anarchist communities and continues that vein of research in her current work on the refusal of social media sites like Facebook—asking whether the choice to stop Liking and checking-in can ever constitute a collective politics or whether it’s just the 2010s version of “Oh, I don’t own a TV.” Many of her participants, and the various anti-Facebook manifestoes that have emerged from these protestors, readily identify the alienation and exploitation on which Facebook’s business model is based. They complain of their time being colonized, their every interaction being commodified by a company whose processes and profits are not shared with its billion-strong user workforce, their conversations and emotions being translated into sterile Likes and shares. But what happens next? Facebook refusers often want to quit so that they can focus on real, important, waged work. Or they use the act of quitting as a status symbol; a case of bourgeois refinement framed against the social excesses of Facebook zombies, often framed in feminized terms of too much flirting and baby pics. As McPherson noted, Portwood-Stacer is here less concerned with whether refusal works—whether it functions as a strike that threatens Facebook—and more concerned with what work refusal does for refusers.

Laura Portwood-Stacer (@lportwoodstacer) just published a book on lifestyle activism in anarchist communities and continues that vein of research in her current work on the refusal of social media sites like Facebook—asking whether the choice to stop Liking and checking-in can ever constitute a collective politics or whether it’s just the 2010s version of “Oh, I don’t own a TV.” Many of her participants, and the various anti-Facebook manifestoes that have emerged from these protestors, readily identify the alienation and exploitation on which Facebook’s business model is based. They complain of their time being colonized, their every interaction being commodified by a company whose processes and profits are not shared with its billion-strong user workforce, their conversations and emotions being translated into sterile Likes and shares. But what happens next? Facebook refusers often want to quit so that they can focus on real, important, waged work. Or they use the act of quitting as a status symbol; a case of bourgeois refinement framed against the social excesses of Facebook zombies, often framed in feminized terms of too much flirting and baby pics. As McPherson noted, Portwood-Stacer is here less concerned with whether refusal works—whether it functions as a strike that threatens Facebook—and more concerned with what work refusal does for refusers.

Portwood-Stacer thus theorized a question with which we were all concerned in one form or another: What does it mean to strike from the social factory? And is ‘strike’ even the right way to think about the relationship between society and value today? She wants us to think past notions of consent and exploitation—after all, we all consent to our EULAs and most refusers acknowledge exploitation but opt out of it instead of rally against it—and ask what free labor feels like, and what it means to tell users they are laborers. She looks towards the historic wages for housework campaigns as a useful corollary. Getting paid for housework was only ever one goal of those campaigns. The real thrust was to show that value is only ever produced via uneven social relations, that corporate profits would not exist without unwaged labor. This is what Kathi Weeks calls the utopian demand: Not just a request for a policy change, but a call to rally around particular social perspective, the distance between this world and another possible one. In this perspective, social media is just the latest development in capitalism’s exploitation of free labor (we could also think about the control of native traditions or our very genes through intellectual property) and the recognition of that relationship is just as important as any call for better privacy, more consent, or pay for free labor.

Voces Móviles and the Precarity of Work in Online/Offline Spaces

Anne Cong-Huyen (@anitaconchita), an important voice in the #transformDH collective, presented a piece of her dissertation research, which focuses on close readings of technological precarity. Here she walked us through the Voces Móviles online storytelling project and work space, which allows migrant day laborers, called ‘reporters’ on the site, in and around Los Angeles to share life histories, working conditions, and photographs. Many are anonymous, some are linked into ongoing narratives, but all work against the sanitized images of Southern California as either sunny paradise or fast-moving media mecca; images which erase the blood and sweat that goes into maintaining those lawns, pools, and offices. Indeed, the creative class lifestyles and consumption-oriented gentrification I reviewed in my presentation would not be possible without the human infrastructure which Voces Móviles makes visible.

Anne Cong-Huyen (@anitaconchita), an important voice in the #transformDH collective, presented a piece of her dissertation research, which focuses on close readings of technological precarity. Here she walked us through the Voces Móviles online storytelling project and work space, which allows migrant day laborers, called ‘reporters’ on the site, in and around Los Angeles to share life histories, working conditions, and photographs. Many are anonymous, some are linked into ongoing narratives, but all work against the sanitized images of Southern California as either sunny paradise or fast-moving media mecca; images which erase the blood and sweat that goes into maintaining those lawns, pools, and offices. Indeed, the creative class lifestyles and consumption-oriented gentrification I reviewed in my presentation would not be possible without the human infrastructure which Voces Móviles makes visible.

In a political climate where day laborers are painted in broad strokes as at best disposable workers and at worst social leeches, Voces Móviles emphasizes the diversity of these communities: their different skills and work environments, different ethnic and national backgrounds, and different struggles with the naturalization process. Indeed this variation emerges in the design of the site, where outsiders struggle to tie the different images, voices, and stories together into coherent narratives. There are thousands of posts, over 660 pages. This work required of the reader reminds them not only of the invisible work of the day laborers but the additional work they take on in order to tell their stories—and forces us to distinguish between different kinds of work and the value placed on each. Again, as with Portwood-Stacer, we see parallels between traditional analyses of social reproduction and newer critiques of free labor online. Voces Móviles also forces us to recognize that the seemingly ephemeral nature of any information economy is always rooted in the material: devices and their construction, service work catering to creatives, but also the time it takes for a body to get off a ladder, take out their phone, snap a picture, and get back to work.

Antiviral Media:

The Market for Primitive Africa in Internet Vigilante Trophy Websites.

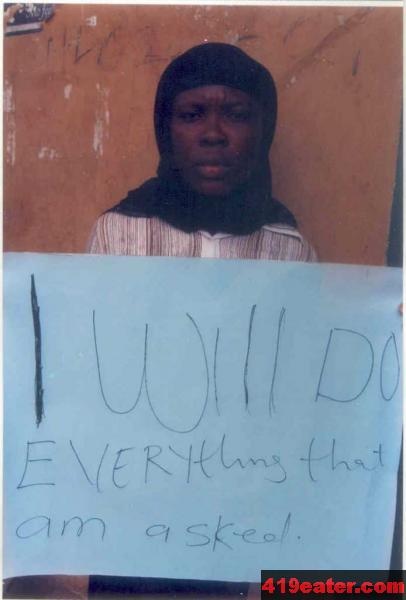

Finally, Lisa Nakamura (@lnakmur) closed the presentations by using the culture of 419eater—a site which documents the various humiliations African internet scammers are subjected to by Western internet users—and other digital pillories to intervene in two debates: media archaeology and the marketing-oriented conversation over ‘spreadable media.’ For Henry Jenkins et al, memes that don’t spread are dead. But Nakamura wants us to remember that memes don’t appear out of thin air, that hate spreads as quickly as laughter and is always culturally bound (e.g., lynching postcards and the Abu Gharib photos could be read as cultural ancestors of the scam baiters), and that some memes deserve to die—we just don’t know how to kill them. So now we have a series of ethical questions: Why share? Why is it better to spread? And what makes something ‘spreadable’ besides technical features that make it easy to send and receive? This is another moment where we’re reminded that what is often labelled as an invasion of the social web—the racism and sexism written off as ‘trolling’—has been there since the beginning; that the colonial relationships re-enacted by the scambaiters are features, not bugs, of global internet cultures. Decolonizing the internet is thus partly about building alternatives to current social spaces. Voces Móviles is one example, but so too Critical Commons, Vojo, and Mukurtu. But this is also a critical project that asks us not necessarily to jump to build another tool but to sit and reflect on how we got where we are.

Similarly, Nakamura critiqued the formalist, Kittlerian media archeology tradition for searching for this or that previously unseen or unknown innovation, the heroic recovery of glitches and roads-not-taken by ‘digital ghostbusters.’ This archaeological urge to excavate and exhibit is a close relative to the abject spectacle of 419eater—where technological backwardness is found, displayed, and made viral—or memes of feminine vulnerability. Here Nakamura is not uncovering some hidden racist agenda in media archaeology or fan studies, but sketching an alternative project that doesn’t separate container from contents and asks after the labor, racialized and otherwise, of spreadable spectacle. This ‘digital archaeology’ would track genealogies of racism and sexism that otherwise seem to just appear from thin air and go viral in different media.

Response and Discussion

I’ve integrated some of McPherson’s (@tmcphers) comments on specific papers into the preceding discussion, but want to sketch out two more themes that emerged from her closing remarks and the discussion that followed.

First, why Marxist feminism in media studies and why now? This was a largely unplanned collective turn that we and our audience found ourselves making together—though it is a turn signaled by work like Weeks’ and a possible renaissance of Marxian political economy across disciplines dominated by poststructuralism in recent decades. Marxist feminism seems better able to cope with the messy materials of everyday technologies than poststructural approaches. Within James, Federici, Dalla Costa and others, we find an intimate understanding of how value is socially produced by marking certain spaces and activities as more or less socially necessary; a keen attention to the collective politics around individual questions of what counts as an act of work, love, or play; and a general attention to the feminization of work and poverty in the current era. They help us ask better questions about who is building our machines and why, whether refusal is consumer democracy or free labor strike, and how the free labor critique can become more politically mobilizing. On that last point, Marxist feminism helps chart a third way between ‘spreadable media’ critiques of social media as empowering (which ignores political-economic relations) and more traditional Marxist critiques of social media as exploitative, alienating labor (which ignores what people actually do online and why they keep doing it).

Second, how do we balance the critique of the platform with that of the social relations in which it is enmeshed? This is an open question. The Californian ideology that dominates our common sense of what information technology is and what it does stresses spreadability but also transparency. But sometimes small is good, growth is dangerous, and the DIY imperfect is more powerful than the smooth and shareable. We can see this with Voces Móviles and similar projects which showcase the messy processes of democratic technologies, but also puncture the fantasy that the commons, technological, intellectual, or otherwise, are every truly open. The free and open commons is, if not a myth, then a “limit case”, for McPherson. And any critical platform studies that we build together must read, analyze, and make with actually existing politics of technological use and abuse in mind, and with an eye to other possible technological worlds—even if they’re only temporary spaces of refusal, privacy, or play.

Great write up and some compelling presentations. Wish i could have been there.

[…] has written a great wrap-up of our panel for the CUNY Academic Commons Digital Labor Group. His Panel Review briefly summarizes each speaker’s presentation. Thanks, […]