By Anne Boyer

Part Two

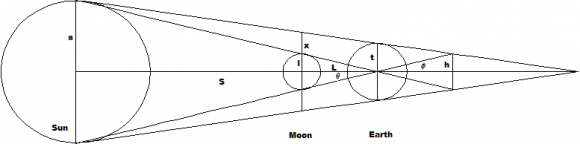

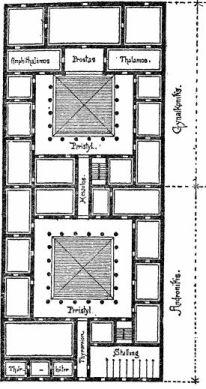

In the 19th century, feminists made plans for kitchenless houses. This was so women would not have to work for free. By ripping the kitchen out of the home these feminists made, through blue prints, a dream of an oikos with a hole in it. It was a dream of a reproductive labor strike built into the dream of a home. Consider these contemporary equivalents to the kitchenless house: What is the architecture for “sex strike”? What cities could be built in such a manner that we will never be told to “smile” again? If there is now this global mega-oikos, what would be the equivalent of the mega-oikos with the kitchen ripped out? As Eric Hobsbawm wrote, “Suppose, then, we construct the ideal city for riot and insurrection…” I wonder “Suppose, then, we construct the ideal oikos for the same.”

If we might imagine a household built for riot, we could, like those 19th century feminists, construct this ideal household through the stubborn ripping out of the heart of the mega-oikos. Like a city with a sinkhole in it, we could make this insurrectionary oikos. Here the household would be looted of what we need (care, love, sustenance) and what is not needed (sexual and familial violence, enslavement, racialized and gendered divisions of labor) is left for the flames. An oikos-built-for-riot and the riot-of-the-oikos in any shape would force what appears to be the polis—the often violently enforced boundary of the oikos—into a significantly different shape, too. The polis itself, so transformed by the transformation of the oikos, would take on its own unique shape: perhaps half daycare center, half insurrectionary terrain.

This scheme of a looted oikos and a polis of rioting toddlers is possibly Hannah Arendt’s nightmare, also the dream made possible by Hannah Arendt. It is this reason that I will address her at some length in this part of my response. As Arendt wrote, “the human heart a place of darkness,” and so, too, can be the “household” as it exists. In this sense I am sympathetic to Arendt, for the mere relocation of reproductive labor as we know it (as in, for example, Occupy) comes to the limit of itself, for it brings along a relocation of the gendered and racialized violence that enforce the boundaries of the polis.

Mitropoulos is a sharp reader of Arendt, sensitive to the weaknesses and contradictions in Arendt’s thinking without being caught up in despair of them, so Mitropoulos reminds us politics also, for Arendt only takes place in plurality. Infrapolitics, the reminder that politics takes place between the people in this plurality, is precisely why the heart as itself is a dim ground for action: politics can’t happen inside of us, only between us. Politics requires infrastructure: what is between, what can exist before us, without us, and after us, too. Mitropoulos asserts that infrastructure can be a contract, and as I argue in my analysis of Xenophon the first part of my response, building on some of Mitropoulos’ ideas, I think, too, that infrastructure can be what is beside the contract: care.

Though care exhibits, in significant ways, contractual elements (or the contract retains elements of care), and care is increasingly subject to as set of brutal hypercontractual arrangements[1], the underlying structure of care—the relation of the household to the household—provides an escape the strict delimitations of what we understand of the contractual. In her notes for this forum, Mitropoulos proposes that “tactical engagement with the world of contracts might not foreclose, and instead encourage, the development of a relationality—a politics and economics of the in-between—that can break with the limits of the contractual.” Care is the possibility of this kind of tactical engagement, developing new, necessary, and materially transformative politics. As it is increasingly forced on us by austerity and social measures to retrench a genealogically formed oikos, we could force it back, creating a “contagious” or leaky oikos. As we learned in the Oikonomikos, a wife can wreck the economy, so then the “wife’s duty”—care, in its deployment, withdrawal, or even, in the case of Ischomachus’ “real” wife, its perverse deployment— has the power to remove the ground in which the contract as we think of it now is founded.

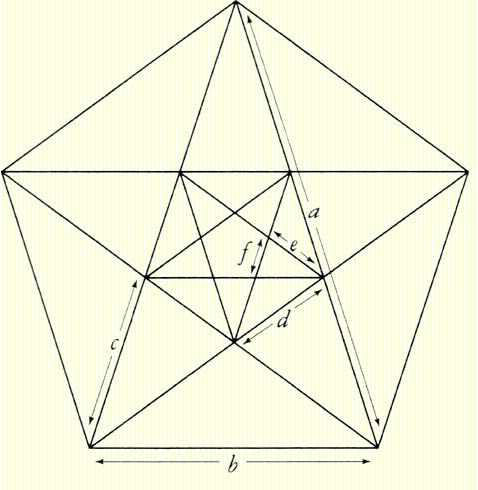

The wage relation enabled by the contract is terrible, but it grants, as Mitropoulos points out, “the compensatory distinction between those with, on the one hand, the authority to contract and those, on the other hand, who laboured under the condition of slavery or unpaid domestic labour.” This is not nothing. Through the ability to enter a contract, then, even out of a slave or woman, a free man was [almost] made. But that this is our available freedom is Capital’s tragedy: care could confer, without the contract’s limits, a new concept of a new political subject created by care’s unique mode of the infrapolitical. A politics based on this seized interrelation could provide a free relation barely imagined as it would require an unloosing from the schemes of domination based on sex, race, lifespan and the schemes of domination brought by property and the wage relation. In this it is this oikos with a sinkhole in it: or to use another Arendtian schema—freedom’s abyss[2]: the “hole” created by a new event, brought about by “the freedom to call something into being which did not exist before, which was not given, not even as an object of cognition or imagination, and which therefore, strictly speaking, could not be known.”

I want to continue to create, somewhat disobediently, a kind of sinkhole in Arendt’s own thinking. In The Human Condition, Arendt writes:

The political realm rises directly out of acting together, the ‘sharing of words and deeds.’ Thus action not only has the most intimate relations to the public part of the world common to us all, but is the one activity which constitutes it. … The polis, properly speaking, is not the city-state in its physical location; it is the organization of the people as it arises out of acting and speaking together, and its true space lies between people living together for this purpose, no matter where they happen to be. ‘Wherever you go, you will be the polis.’

I would like to consider the possibility located in Arendt, but also beyond her, that the “sharing of words and deeds” she located in the polis can also be the “sharing of the words and deeds” that is the care that occurs in the oikos. Care is action—even, though Arendt was not able to see this, in the Arendtian sense—and care is also a method of organization of the people as it arises out of acting and speaking together. “Wherever you go, you will be the oikos, too.”

Care is only removed from the realm of action and potential freedom when it is forcibly extracted through violence, slavery, “love,” and social limitations upon those who are required to give it. But it is important to say that “care” bears no more natural relation to this “indoor body” as subject of violence than a woman’s body actually bears to a person who must remain indoors. The arrangement in which we must give or receive care is historical, not natural, and the primacy of the contract as political infrastructure is not uncontestable. Care as we know it is brutally managed through contracts, violence, and the theatre of the marketplace because the infrastructure provided by care provides a real risk to what we know as politics. Care is not a symmetrical relation, or even a semi-symmetrical one like the fraternal performance of contracts: instead, it is atomic, shifting, unfixed, perpetually transformed, not limited to the human subject, but extended in relation to the world of objects and environments. Care, then, is the infrastructural method that rather than attempting to always insure against the aleatory, asserts its own potential to out aleatory-the-aleatory. Constantina Zavitsanos pointed out in a response to an earlier draft, care, as the relation of life and death, surpasses even the bonds of affection: even our enemies require it to live.

What happens in the oikos is important: we need to be born, to give birth, to make love, to eat, to sleep, to have bodies, to be sick, to be cared for, to comfort each other when sad or wounded, to experience joy together, to be mourned when we die. Arendt sees this, but she fails at the moment she asserts, axiomatically, that these things must necessarily be private so that the public can be public. This prescription is the failure that comes from Arendt’s fidelity to historical description: for a thinker who understands better than any other the “miracle,” she was, in this, remarkably closed to the one I would propose.

Imagine this: not the oikos of Xenophon—no estate of crude walls, violence or the threat of it, no site of exploited unwaged labor, racialized terror, gendered violence, or other waking nightmares of the private; not the oikos as it creates the condition for the terrible wage with its wagelessness, and its wagelessness creates, also, the desire to contract—to be, despite this freedom’s obvious limitations, “free”; not the political actor of Machiavelli, machinated by “domestic tyranny” and terrorized by “effeminacy” who must self-manage through the management of everyone else; not a quasi-polis full of the political actors of Althusser, Strauss, Negri, and others who Mitropoulos points out rely on “a definition of political agency in masculine terms.”

Imagine instead that leaky mega-oikos, contagious with care, ready for riot, taking a new shape and forcing this shape into the polis, dispersing and swerving, like the dream of a kitchenless house of the 19th century—a mega-oikos in the shape of what Mitropoulos calls “a promiscuous infrastructure.” Here, Mitropoulos gets to the point which most compels my thinking: “In the seemingly tangential arguments over how to organize the labor that goes in to sustaining the occupations, how to arrange kitchens, energy, medical care, shelter, communications and more, in the correlations between homelessness and #occupy encampments, in the very questions posed of how to take care of each other in conditions of palpable uncertainty, live the pertinent issues of the oikos of in these times.”

These questions are, to me, not only posed by encampments and occupations, though it has been in these moments recently that we have found our failures and from these failures our potential strategies. Indeed, “how to arrange” ourselves and our infrastructure is the question forced back at us at every turn by this minute of history: it is as much a question posed by the blockade or the riot as it is the occupation, it is as much a question posed by the struggle in the home or for a home as it is in the struggle in the workplace and the streets. It is there when we are sick and there is no one to care for us or our people are sick and we are not there to care for them or when we have no people at all; it is there in the ports and shipping hubs; it is there in our digitized labors and the industrial and reproductive labors that support them; it is there in the leveler of an unstable climate that increasingly turns even what we might think of the polis into an urgent site of necessary care and renders the oikos as shelter for no one. The leaky oikos can be what abolishes the distinction between oikos and polis itself. The horizon presented by oikopolitics is the horizon of anti-politics. Care is the question forced on us by capital. It will not go unanswered, but as we are as much history as anyone, it is what we must answer ourselves.

As Silvia Federici wrote in the closing essay of Revolution at Point Zero, “If the house is the oikos on which the economy is built, then it is women, historically the house workers and house-prisoners, who must take the initiative to reclaim the house as a center of collective life.” But the house women and others historically positioned in the oikos must claim now will be the one with the old walls dismantled, with the kitchen ripped out, with the dream of the insurrection built into its architecture, with the sinkhole in the middle, with the knowledge that the polis itself will be infected by new infrastructures, radically breached. A friend recently told me, “Contracts are for capitalists, lawyers, fathers; promises are for militants, lovers, friends.” Our care must become our weapon. Contracts will be broken; care must persist. Wherever we go, we will be the oikos, but it is in this, and its possibilities, there is the promise that a future we want might exist.

[1] For more on these historical developments in the U.S. and their effects on women and the poor, see Gwendolyn Mink’s Welfare’s End.